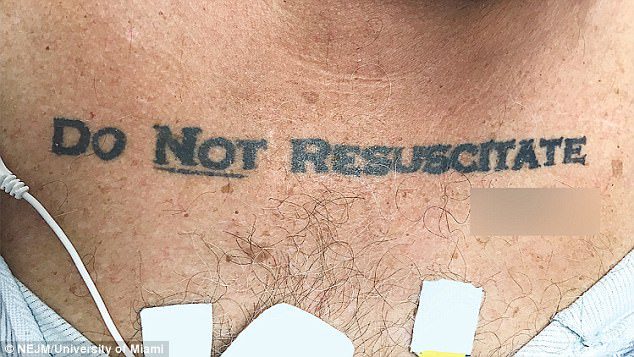

A 70-year-old man was unconscious and presumably drunk, given his elevated blood-alcohol level, when paramedics brought him to the emergency room. The man’s ‘do not resuscitate’ tattoo forced Miami emergency doctors to confront the ethical conflict between a patient’s wishes and a doctor’s duty.

When his pulse slowed to a worrying rate, the doctors decided to try to save him anyway, but were getting no response according to a case study published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

After the doctors consulted with ethicists, they decided to respect the man’s tattoo, but the quandary made them aware of the need for an updated system of tracking patients’ end of life wishes.

After finding him on the street, paramedics brought the senior to the University of Miami hospital emergency room.

A 70-year-old unconscious man with ‘do not resuscitate’ tattooed on his chest (pictured) alongside what appeared to be his signature. He had no other identification or next of kin, so Miami doctors had to decide whether or not to respect the man’s inked wishes

The man couldn’t be roused and had alcohol in his system, but none of that was terribly unusual.

‘Unfortunately, we get a lot of that kind of patient at my hospital,’ says Dr. Greg Holt, one of the doctors who treated the man.

The man’s tattoo was unique enough to draw the attending physician Dr. Holt, and his entire team of eight down to the emergency to see what the fuss was all about.

The man had a signed ‘do not resuscitate’ on his chest, with a line under the ‘not’ for emphasis.

‘We always kind of joked around about doing that. A lot of physicians say “Boy, I’m going to have that tattooed on my chest so everyone knows my status.” Then you see it and…holy crap,’ says Dr. Holt.

The team’s first concern was legality. Tattoos are not legally-binding DNR orders. Dr. Holt said there are very specific requirements for legal orders in Florida.

‘It has to be on yellow paper, both the doctor and the patient have to have signed it…it doesn’t say anything about tattoos.’

DNR orders are protected by medical privacy laws, and about 80 percent of Americans with chronic illnesses reported that they did not want to be hospitalized or put into intensive care if they were dying.

People who want DNRs have to fill out standard forms with their doctors. Then, the DNR is written on the medical chart, and they can get bracelets or wallet cards showing their status. These wishes are usually reiterated in a will.

Dr. Holt’s patient blood pressure dipped dangerously low and his team decided that it was better not to risk the outcome that could not be undone: death.

They gave the patient IV fluids, antibiotics, and ‘some medications to keep his blood pressure up, which some people would consider resuscitation,’ says Dr. Holt. ‘If I knew that he was no code, I would have put him on a breathing machine,’ Dr. Holt adds.

But with a tattoo, ‘I always kind of thought people might regret it later on, you get drunk, you get it when you were a kid, you wish you didn’t, but what can you do?’ says Dr. Holt.

In another case study, a diabetic patient had gotten ‘D.N.R.’ tattooed on his chest (pictured) after losing a bet, but said it did not reflect his wishes

In another case study, doctors discovered a tattoo reading ‘D.N.R.’ on the chest of a diabetic man in the hospital for a leg amputation. When his doctors asked about the ink, the man said that it was the opposite of his wishes.

The patient, a hospital worker had lost a bet when he was younger, agreed to the tattoo but, according to the case study, ‘did not think anyone would take his tattoo seriously.’

Dr. Holt says his patient’s tattoo seemed different.

The hospital’s ethics team consulted with the doctors, and together they decided that the tattoo most likely did represent the patient’s true wishes. The man’s apparent signature was included.

Dr. Holt also says the placement of the tattoo mattered. ‘It was exactly where you would have to do chest compression, the guy had to have had some knowledge of the medical system,’ he says.

The team was confronting a deeper question.

‘One way is to say “we don’t know [his wishes] so forget [the tattoo]”. The other way is to say we are being too dogmatic,’ says Dr. Holt.

He says that ‘it’s really hard for patients to have their end of life wishes known,’ and this man, he and the ethics team concluded, had taken matters upon himself, literally.

Two hours later, they found documentation confirming that the tattoo was correct and the man had signed a DNR order.

The patient took a turn for the worse, and the doctors let him go, but it was a wake-up call to Dr. Holt.

DNR orders are still on paper, and the man could have changed his mind after getting his tattoo, patients may change their minds before having an opportunity to change their resuscitation status.

‘It’s a concern for both physicians and patients because you want to do right by someone and if you don’t know, you do everything you can think of because we always pick the reversible choice, not the one you can’t take back when faced with uncertainty,’ he says.

If you know someone who might like this, please click “Share!”